- Harpy eagles are the only species in their genus.

- Harpy eagle pairs mate for life.

- They are the national bird of Panama.

About the Harpy Eagle

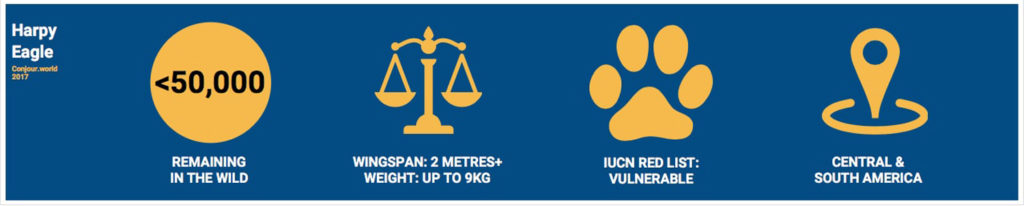

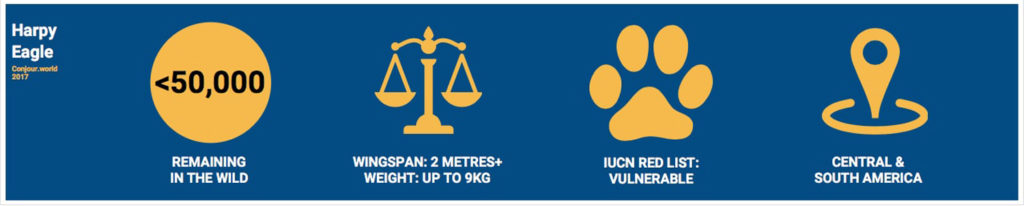

It is difficult to convey the sheer enormity of the Harpy eagle through words alone. As one of the largest raptors in the world, the species can weigh up to nine kilograms (20 pounds) and some specimens have been found to have a wingspan in excess of two metres (seven feet). If this wasn’t impressive enough, the eagle’s giant talons can exert over 50Kg pressure, which makes it easy work to snatch and crush the bones of the small monkeys and sloths that live in the rainforest canopy.

The Harpy eagle used to be found throughout Mexico, Central America and South America, but now due to declining numbers, they are rarely found in this range and are most commonly located in Brazil. The Harpy eagle habitat is tropical lowland rainforests. Living in the treetops the raptors hunt in the canopy, using tree branches as perches to scan the forest for prey. Perfectly adapted for hunting in the rainforest, the eagles have developed a smaller wing and longer tail ratio, which allows them to quickly manoeuvre at high speed in the treetops.

They are avid hunters and, with no natural predators, they are themselves an apex predator of the rainforest. They are diurnal hunters meaning they only hunt during the day, using daylight to sit in the canopy and scan the surrounding forest for prey. Once prey has been spotted the eagles launch themselves at their target, and reaching diving speeds of over 80km/h snatch the creature effortlessly. Death is often instant for the prey as the eagle uses its hugely powerful talons to crush the skull. They normally hunt small prey between seven and eight kilograms in weight.

The remains of sloths, monkeys, tropical birds and livestock have all been found in abandoned harpy nests.

The Harpy Eagle Lifecycle

The females are significantly larger and can grow up to twice as large as the males of the species, making them easily distinguishable. Besides this difference in size, there are few differences between the sexes. Both possess the signature double crest on the back of the head and males and females have identical plumage: grey/slate feathers cover the wings and back whilst the abdomen is covered in white feathers.

When it comes to mating, Harpy eagles mate for life. Eagles begin to seek a mate when they reach four to five years of age, and a successful pair can spend up to 20-25 years together. They are very particular in their nest building and often build their nests in the crown of the Kapok tree, one of the tallest trees in South America. Nests are normally built above 40m in the tree canopy and both partners are heavily involved in scavenging surrounding trees for branches to build it. Nests have been found to be as large as a double bed – they are sturdy structures and a mating pair will often use the same nest several times.

Once the nest is built the female will normally produce one to two eggs per mating season. She then adopts an incubation role whilst the male hunts. The eggs are incubated for 55 days and once the first egg hatches the other is ignored: Harpy eagle chicks require a lot of feeding and so the parents will solely invest in one chick to increase the rates of survival. During eaglet rearing the male must constantly hunt, as both female and chick must be fed. The chick requires a lot of energy, as it will grow to full size within around six months, at which stage it will fledge. However, hunting is a skill that takes two or three years to learn and so the parents will still supplement the chick’s diet with their own kills until then (Watson et al 2016). Parenting the chick is a full-time job for the pair.

Harpy eagles are an essential part of the tropical rainforest ecosystem. As Apex predators who actively hunt, the species ensures that the arboreal and land mammals of the rainforest do not become overpopulated, which would lead to the vegetation being depleted by grazing. To put it simply, extinction of the eagle could have devastating effects on the whole forest ecosystem.

Harpy Eagle Conservation

Unfortunately, the Harpy eagle population is on the decline. The species is now on the verge of extinction in Central America, and numbers of mating pairs have slowly been disappearing throughout the habitat. This decline is almost certainly due to human activity.

Deforestation has had a devastating effect on rainforest across Central and South America. The rainforest has become a primary target for the development, logging and cattle industries – all of which clear the forest to create pastures for livestock. In recent years, deforestation has resulted in a huge loss of rainforest, meaning that the viable habitat for the Harpy eagle species has vastly declined and hunting territory is in danger of disappearing. As Harpy eagles need to hunt daily when rearing a chick, loss of habitat can result in mating couples starving to death.

IUCN assessments have found that the species has lost up to 45.5% of its habitat over the past 56 years, which led the IUCN red list to label the species as “Near Threatened” in 2012. CITES also assessed the species as “threatened with extinction”. It is estimated that less than 50,000 individuals remain in the wild.

The second largest threat to the Harpy eagle population is the danger of being hunted. Locals tend to hunt and shoot the eagle as its large size has led to fears the eagle may prey on domestic livestock, although documented cases of this occurring are extremely rare. Some local people also use Harpy eagle feathers in headdresses as part of their cultural traditions. As Harpy eagles only raise one chick with every mating season (2-3 years), this hunting can rapidly damage the reproduction rate of the species.

Unless the rapid rate of deforestation is halted, and the poaching numbers decline, this species will quickly be in danger of disappearing completely.

The Peregrine Fund

Dr Rick Watson, Vice President & International Programmes Director of The Peregrine Fund, is well placed to speak on the Harpy eagle’s endangerment. The Peregrine Fund is currently running several projects to help conserve the species.

Deforestation and habitat loss are having a disastrous effect on all forest species in the area. Dr Watson explains that because Harpy Eagles exist at low density to start with, the impact on their population is greater.

His organisation has been heavily involved with the conservation of the species. The team of biologists set up a restoration project in Darian, Panama using captive breeding and release. This project was initially a success, although it did highlight that we have a lot to learn about the species, and further adaptation of the project would be needed to increase the success rate. This was mainly due to the long post-fledging dependence of the eaglet.

Dr Watson explains that although this project was initially successful, it was assessed that the project resources would have more of an effect in reducing the eagle decline if they were used to prevent shooting and habitat loss.

The Peregrine Fund biologists are now working closely with the indigenous Embera-Wounaan communities to reduce deforestation and shooting. Community-based conservation projects have been set up to teach the local population about alternative farming and grazing systems that promote biodiversity conservation in multiple use zones around Darién National Park.

Dr Watson is hopeful that these projects, working with the local people will promote and conserve Darién’s lowland moist tropical forest and biodiversity by addressing and teaching the community about the negative impacts of uncontrolled cattle ranching, agricultural encroachment, and bushmeat extraction. Similar programmes are also being run to explain the ecological importance of the eagle and the effect of hunting and poaching the species on the wider ecosystem.

For the Harpy eagle to survive in the coming years, it is essential that effective education programmes are set up to educate the local population and create a mutual relationship between the people and the rainforest. You can help the species thrive in the future by contributing to The Peregrine Fund’s work.

Reference:

Trial Restoration of the Harpy Eagle, a Large, Long-lived, Tropical Forest Raptor, in Panama and Belize Author(s): Richard T. Watson, Christopher J.W. McClure, F. Hernán Vargas, and J. Peter Jenny Source: Journal of Raptor Research, 50(1):3-22. URL: http://www.bioone.org/doi/full/10.3356/rapt-50-01-3-22.1.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login